The Role Of Gut Health In Disease Prevention – How To Improve The Microbiome

Gut health has been gaining more attention in recent years due to its impact on overall health and well-being. Our gut, also known as the digestive system, plays a critical role in not only digesting food but also in maintaining our immune system and protecting us from diseases.

The gut is home to trillions of bacteria, most of which are harmless or even beneficial to our health. These bacteria, also known as the gut microbiome, help break down food, produce essential vitamins and nutrients, and prevent harmful bacteria from thriving in our bodies.

However, when the balance of these bacteria is disrupted due to poor diet, stress, antibiotics or other factors, it can lead to an unhealthy gut and increase the risk of various diseases. Research has linked an unhealthy gut to conditions such as obesity, autoimmune diseases, allergies, and mental health disorders.1

The Role Of Gut Health In Disease Prevention

A healthy gut has been shown to have many benefits for our overall health. One of the main ways a healthy gut prevents disease is through its impact on the immune system. Around 70% of our immune system resides in the gut, and a healthy gut microbiome plays a crucial role in keeping it balanced and functioning properly.

A strong immune system is essential for fighting off pathogens and preventing diseases. The gut microbiome helps train our immune system to recognize harmful bacteria and activate an appropriate response. It also produces short-chain fatty acids that have anti-inflammatory properties, further supporting the immune system.2 3

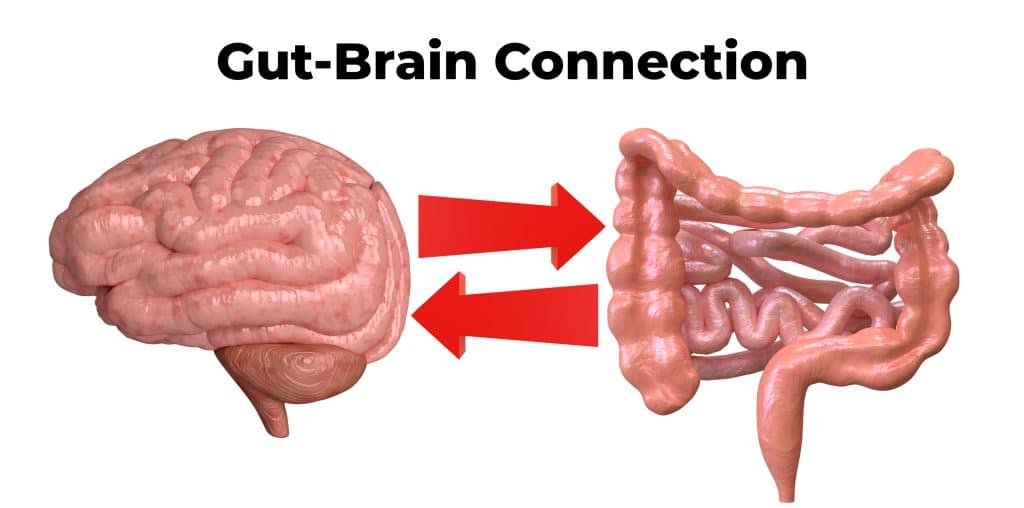

The Gut-Brain Connection

In addition to immune system support, a healthy gut also plays a role in regulating hormones and neurotransmitters that affect our mood and mental health. The gut microbiome produces various neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA, which are essential for regulating mood and emotions. An imbalance in these neurotransmitters has been linked to conditions such as depression and anxiety.

Moreover, the gut-brain connection goes both ways, with the brain also influencing gut health. Stress and other psychological factors can disrupt the balance of bacteria in the gut, leading to digestive issues and other health problems.4

Gut Health And Disease Prevention – Heavy Metal Toxicity

Heavy metal toxicity causes gut health deterioration. The disruption of the microbiome can lead to serious health problems such as nutrient malabsorption, chronic inflammation, and autoimmune diseases. Heavy metals are ubiquitous environmental contaminants that are found in water, air, food, and soil.

Some of the most common heavy metals that we are exposed to include lead, mercury, cadmium, and arsenic. These metals have been shown to accumulate in the body over time and can cause serious health issues. Heavy metal toxicity has been found to affect the diversity and functions of gut microbiota. Studies have shown that heavy metals can alter the abundance and composition of gut bacteria, leading to dysbiosis.

This disruption in the microbiome can affect the production of essential metabolites which play a critical role in maintaining intestinal health. Additionally, heavy metal exposure can also promote the growth of pathogenic bacteria, leading to an imbalance in the gut microbiota.

Moreover, heavy metals are known to induce oxidative stress and damage to intestinal epithelial cells, which can compromise the integrity of the gut barrier. This can result in increased permeability and translocation of harmful bacteria and toxins into the bloodstream, causing systemic inflammation.

The relationship between heavy metal toxicity and microbiome dysbiosis is bidirectional. While heavy metals can disrupt the gut microbiome, an unhealthy microbiome can also increase the absorption of toxic metals.5 6

Read more about removing heavy metals from the body.

Gut Health And Disease Prevention – Antibiotic Abuse

One major factor that can contribute to gut health issues is the use of antibiotics. While these medications are essential for treating bacterial infections, they can also have a significant impact on our microbiome. Antibiotics work by killing or slowing the growth of bacteria, but they do not discriminate between harmful and beneficial bacteria.

This indiscriminate killing of bacteria can lead to an imbalance in the microbiome, as certain species may be more susceptible to the effects of antibiotics than others. This can result in a decrease in the diversity of microbial communities, which is associated with various health issues.

Studies have shown that alterations in the gut microbiome due to antibiotic use can increase the risk of developing conditions such as obesity, allergies, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Furthermore, the effects of antibiotic use on the microbiome can be long-lasting. Even after completing a course of antibiotics, it can take weeks or even months for the microbiome to fully recover. In some cases, the microbiome may never fully return to its original state.

To mitigate these negative impacts on our microbiome, it is important to only use antibiotics when necessary and to follow the prescribed course of treatment. Additionally, incorporating probiotics and prebiotics into our diet can help restore balance in the microbiome after antibiotic use.7

Gut Health And Disease Prevention – Pesticide Exposure

Another cause of dysbiosis is exposure to pesticides, which can have detrimental effects on both the gut microbiome and human health. Pesticides are chemicals used in agriculture to protect crops from pests, weeds, and diseases. While they may be effective in increasing crop yield and preventing food shortages, their use has been linked to negative impacts on human health. Pesticides can enter the body through various routes, such as consumption of contaminated food and water, inhalation, or skin contact.

Pesticides, like glyphosate, have been shown to disrupt the balance of the gut microbiome, leading to dysbiosis. This disruption can occur through several mechanisms such as altering the composition of gut bacteria or reducing their diversity. Studies have shown that exposure to pesticides can lead to an increase in harmful bacteria and a decrease in beneficial bacteria in the gut, resulting in an imbalance that can have negative consequences on gut health.

Reducing pesticide exposure is crucial for ensuring a healthy balance of the gut microbiome. This can be achieved by choosing organic produce, while supporting sustainable farming practices.8 9

Gut Health And Disease Prevention – Improving The Microbiome

One way to improve the microbiome is through diet. Certain foods, such as fermented foods and fiber-rich fruits and vegetables, can help promote the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut. This is because these types of food contain prebiotics which are non-digestible fibers that serve as a food source for beneficial bacteria to thrive on.

Another way to improve the microbiome is through the consumption of probiotic-rich foods. Fermented foods are a great source of probiotics, including yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, kombucha, and tempeh. Consuming these foods regularly can help boost the population of beneficial bacteria in the gut, which can improve digestion, immune function, and overall health.10

In addition to diet and probiotics, there is also ongoing research on how lifestyle factors such as stress levels, sleep patterns, and exercise can impact the microbiome. Studies have shown that chronic stress can alter the composition of gut bacteria, leading to negative health effects. On the other hand, regular exercise has been linked to a more diverse and healthy microbiome.11

Beyond these external factors, there is also interest in manipulating the microbiome through medical interventions. This includes procedures like fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), where healthy fecal matter from a donor is transplanted into the gut of someone with an imbalanced microbiome. FMT has shown promise in treating certain conditions such as Clostridium difficile infection and inflammatory bowel diseases.12

How Fasting Can Improve Gut Health

Fasting gives our digestive system a break from constantly processing food and allows our gut to reset and heal. While fasting, the production of stomach acid and digestive enzymes decreases, giving the gut time to repair any damage and expel harmful bacteria.

Additionally, fasting promotes autophagy, a process where our cells recycle damaged or dysfunctional components. This process extends to our gut lining, helping to remove any damaged cells and stimulate new cell growth. This renewal of the gut lining can improve its function and integrity, reducing the risk of leaky gut syndrome.13 14

There are various ways to incorporate fasting into our routine, such as intermittent fasting, prolonged fasting, or time-restricted eating. However, it is crucial to choose a method that works best for your body and lifestyle.

Intermittent fasting involves cycling between periods of eating and fasting, typically on a daily or weekly schedule. This method has shown to improve gut health by reducing inflammation and promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut.

Prolonged fasting, also known as water fasting, involves consuming only water for an extended period, usually 24-72 hours. This type of fast can provide a more significant reset for the gut microbiome and promote autophagy.

Time-restricted eating involves limiting food intake to a specific window of time each day, typically 8-12 hours. This method has shown to benefit gut health by reducing inflammation and improving insulin sensitivity.15

Read more about the health benefits of fasting.

The Role Of Gut Health In Disease Prevention – Improving The Microbiome

Gut health plays a significant role in our overall health and well-being. By promoting a healthy gut microbiome, we can support our immune system, regulate hormones and neurotransmitters, and prevent various diseases.

Read more about the connection between the microbiome and autoimmune conditions.

References

1 Allaband C, McDonald D, Vázquez-Baeza Y, Minich JJ, Tripathi A, Brenner DA, Loomba R, Smarr L, Sandborn WJ, Schnabl B, Dorrestein P, Zarrinpar A, Knight R. Microbiome 101: Studying, Analyzing, and Interpreting Gut Microbiome Data for Clinicians. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan;17(2):218-230. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.09.017. Epub 2018 Sep 18. PMID: 30240894; PMCID: PMC6391518.

2 Wiertsema SP, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Garssen J, Knippels LMJ. The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients. 2021 Mar 9;13(3):886. doi: 10.3390/nu13030886. PMID: 33803407; PMCID: PMC8001875.

3 Blaak EE, Canfora EE, Theis S, Frost G, Groen AK, Mithieux G, Nauta A, Scott K, Stahl B, van Harsselaar J, van Tol R, Vaughan EE, Verbeke K. Short chain fatty acids in human gut and metabolic health. Benef Microbes. 2020 Sep 1;11(5):411-455. doi: 10.3920/BM2020.0057. Epub 2020 Aug 31. PMID: 32865024.

4 Strandwitz P. Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res. 2018 Aug 15;1693(Pt B):128-133. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.03.015. PMID: 29903615; PMCID: PMC6005194.

5 Bist P, Choudhary S. Impact of Heavy Metal Toxicity on the Gut Microbiota and Its Relationship with Metabolites and Future Probiotics Strategy: a Review. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2022 Dec;200(12):5328-5350. doi: 10.1007/s12011-021-03092-4. Epub 2022 Jan 7. PMID: 34994948.

6 Assefa S, Köhler G. Intestinal Microbiome and Metal Toxicity. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2020 Feb;19:21-27. doi: 10.1016/j.cotox.2019.09.009. Epub 2019 Sep 30. PMID: 32864518; PMCID: PMC7450720.

7 Ramirez J, Guarner F, Bustos Fernandez L, Maruy A, Sdepanian VL, Cohen H. Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020 Nov 24;10:572912. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.572912. PMID: 33330122; PMCID: PMC7732679.

8 Rueda-Ruzafa L, Cruz F, Roman P, Cardona D. Gut microbiota and neurological effects of glyphosate. Neurotoxicology. 2019 Dec;75:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2019.08.006. Epub 2019 Aug 20. PMID: 31442459.

9 Aitbali Y, Ba-M’hamed S, Elhidar N, Nafis A, Soraa N, Bennis M. Glyphosate based- herbicide exposure affects gut microbiota, anxiety and depression-like behaviors in mice. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2018 May-Jun;67:44-49. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2018.04.002. Epub 2018 Apr 7. PMID: 29635013.

10 Wieërs G, Belkhir L, Enaud R, Leclercq S, Philippart de Foy JM, Dequenne I, de Timary P, Cani PD. How Probiotics Affect the Microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020 Jan 15;9:454. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00454. PMID: 32010640; PMCID: PMC6974441.

11 Conlon MA, Bird AR. The impact of diet and lifestyle on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrients. 2014 Dec 24;7(1):17-44. doi: 10.3390/nu7010017. PMID: 25545101; PMCID: PMC4303825.

12 Yin, Y., Wang, T. H., & Tan, C. S. (2020). Fecal microbiota transplantation for autoimmune diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 35(4), 748–758. doi:10.1111/jgh.14919

13 Bagherniya M, Butler AE, Barreto GE, Sahebkar A. The effect of fasting or calorie restriction on autophagy induction: A review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2018 Nov;47:183-197. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2018.08.004. Epub 2018 Aug 30. PMID: 30172870.

14 Larrick JW, Mendelsohn AR, Larrick JW. Beneficial Gut Microbiome Remodeled During Intermittent Fasting in Humans. Rejuvenation Res. 2021 Jun;24(3):234-237. doi: 10.1089/rej.2021.0025. PMID: 34039011.

15 Karakan T. Intermittent fasting and gut microbiota. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019 Dec;30(12):1008. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2019.101219. PMID: 31854304; PMCID: PMC6924599.